3S is the abbreviation for “Seiwa Scholars Society,” which consists of the past and current Inamori Research Grant recipients. The 3S has evolved since 1997 with the hope that the interactions among the various specialties of the 3S members can lead to the further development of the research of their own. In the series “Visiting 3S Researchers,” we interview researchers in 3S who are very active in a variety of fields. The 14th interview is with Dr. Megumi Sasaki (2022 Inamori Research Grant Recipient) from Health Care Center, Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology.

A transitional stage between childhood and adulthood, adolescence is a period when one is relatively prone to mental instability. This is especially so for college students, who, upon admission, suddenly find themselves in drastically different environments. Some experience mental health challenges and struggle to adapt to student life. While most universities have established on-campus consultation centers for students, systematic knowledge about the mental health of higher education students remains limited compared to that of elementary and secondary school students. Dr. Megumi Sasaki, Associate Professor, Health Care Center, Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST), conducts research to develop better ways to support these students while also handling their consultations. We visited Dr. Sasaki at her office for an extensive interview.

How to Safeguard College Students’ Mental Well-Being

── Could you tell me why research on college students’ mental healthcare is so important?

Dr. Sasaki (title omitted below) College students are at the final stage in the process of becoming independent adults, both nominally and in reality. Many of them grow in different ways as they navigate various paths through new experiences, living away from home both physically and time-wise. While this period offers significant growth potential, their state of mind often wavers between that of an adult and a child.

One international epidemiological study on the mental well-being of college students shows that approximately 30% of first-year college students meet the diagnostic criteria for some form of mental disorder over a twelve-month period. Other epidemiological studies report about 20-30% of first-year college students meet these criteria, with at most 30% receiving treatment or support. These numbers must not be overlooked. When students experience mental illness, they may struggle to attend classes, leading to failed credits, or lose opportunities to gain experiences unique to adolescence, placing them in a difficult situation. Schools are being called upon to identify students with such risk factors to start supporting them early.

For the past few decades, there has been relatively steady progress in fact-finding surveys and mental health care for elementary and secondary education, but not much advancement has been achieved in systematized research and practice on the topic for higher education. After the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a project team to survey college students’ mental health about 10 years ago, a body of knowledge based on large-scale research projects has been built up little by little. I’m doing research here at the Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST), a unique graduate university where most of our students are science and engineering majors, and half of the student body consists of international students. Because of this, when I came here, there was little previous research to reference. In order to support the students at JAIST effectively, I needed to begin by gathering data to build a foundation of research findings, in addition to routine practice.

── How do you conduct your research?

Sasaki We ask students about their mental health or if they have any issues by distributing a questionnaire at the time of enrollment and during regular health checkups. The primary purpose of the survey is to identify students with a high risk of mental health disorders and provide early follow-up. With their consent, we also use the data thus collected for our research. One of the survey questions asks about their desire to use the student counseling service, which we deliberately included to encourage students who feel uncertain about college life to visit our office for counseling.

During counseling sessions, we carefully observe students to get to the bottom of the nature of their troubles and issues, which provides food for thought to our work.

── What has your research at JAIST revealed?

Sasaki For the research project I was working on immediately before the research topic for which I received the Inamori Research Grant, I conducted a tracking study of first-year students to examine the background factors contributing to a decline in their mental health scores one year after enrollment. The study indicated that Japanese students tend to be in poorer mental health at the time of enrollment compared to international students. We offer early support to such students who are in poor condition from the outset. When analyzing the profiles of students whose mental symptom scores were low at entry and deteriorated after one year, we found that some were international students with low scores on “positive future orientation” metrics.

This study alone does not help us determine why international students’ mental health often worsens while in school. From insights gathered through counseling sessions with students, it appears that international students are more prone to exacerbated mental symptoms due to a distinct set of challenges compared to their Japanese peers. These include anxieties related to language and cultural differences, as well as concerns over financial stability if they need to repeat a year (as suspension of scholarship payments could jeopardize their very livelihood), in addition to a heavy school workload. Supporting international students requires taking into account the unique stressors they face.

“Positive future orientation” is one of the conceptual elements of psychological resilience. You can say that you are positively future-oriented if you set your own goals, are working to reach said goals, and think positively about the future. As a school counselor, I have always felt that students without clear-cut goals are more likely to struggle with adjustment during college life. Think about it. College students are kept busy with so many tasks every day. It’s no surprise they lose their motivation to learn if they don’t have clear goals. Instead, they begin to question themselves: “Why am I going through this difficulty?” Without a reason to push themselves, they may lose their drive. If they go on to university or graduate school simply because people expect them to or many students of their age do so, they might experience such setbacks. Finding the “ideal you” isn’t easy, and the “ideal” may shift as they grow older. To maintain mental health, it’s crucial to keep searching for what that ideal means to them.

For the research topic for which the Inamori Foundation offered me a research grant, I decided to include a new factor, “procrastination,” to find how it relates to mental health. By definition, procrastination is the act of delaying something even though individuals know it could lead to worse outcomes. We’ve all experienced this state of mind, but if it becomes serious, it can interfere with daily life, including schoolwork. Many students come to me almost every day seeking advice on this issue. Faculty members, too, often tell me they struggle to handle such students, which convinced me that this problem needs further investigation. Previous research on procrastination, both in Japan and abroad, has included intervention studies aimed at changing (reducing) procrastination. However, a common issue was the low completion rate (the percentage of persons who finish the program) of these intervention programs. I had a sense that directly changing procrastination is not easy. This led me to consider how I could help students become better prepared to address their procrastination.

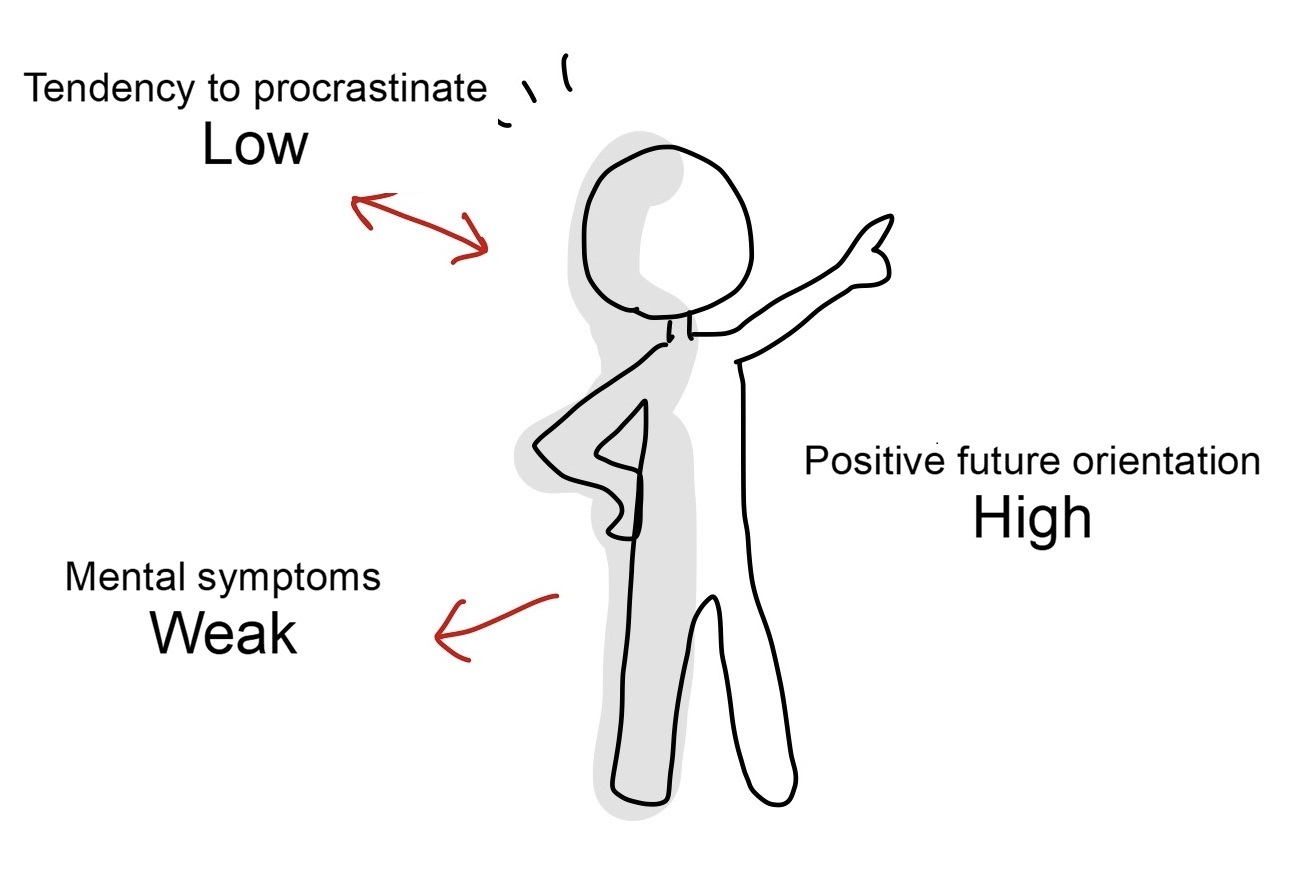

Dialogues with students gave me the impression that those prone to procrastination often have ambiguous purposes and goals. So, I looked at the relationship among procrastination, positive future orientation, which I explained earlier, and mental health. It suggested that positive future orientation and procrastination are negatively correlated (one gets weaker when the other gets stronger) and that the stronger the positive future orientation, the weaker mental symptoms become (see the illustration below).

We also observed a tendency for a stronger inclination to procrastinate to correlate with more severe mental symptoms, although this relationship is relatively weaker compared to the correlation with positive future orientation.

── It sounds to me like being positively future-oriented is the key to maintaining mental health.

Sasaki I wouldn’t say it is a panacea, as there’s a natural limit to how many questions we can include in a single survey without overburdening students. That said, I believe it’s fair to say that we’ve found a key to addressing students’ mental health. While further detailed research is needed, one thing is clear: we need education and guidance that foster positive future orientation in students.

For instance, through first-year education and career guidance at the undergraduate level, as well as private consultations and guidance on education and research at the undergraduate and graduate levels, we can help students identify their strengths and goals and visualize the steps to achieve them, offer positive feedback and facilitate a series of small successful experiences. These efforts, I believe, can foster a more positive future orientation. Moving forward, we will continue collecting and analyzing data to scientifically validate the effectiveness of these supportive measures.

The Significance of Validating Human Mind Scientifically

── How do you feel about the results?

Sasaki My initial impression was that the data allowed me to partially validate what I had always sensed during student counseling. In psychological research, we rarely have discoveries that overturn prevailing social norms. Rather, I think one of the true joys of doing psychology lies in using data to clearly demonstrate phenomena that people vaguely sense in daily life or to explain the process behind a certain phenomenon. With data, you can be more persuasive, making it easier to draw up actions and make big decisions by involving people from other disciplines.

Furthermore, publishing our findings as research papers could allow them to contribute to other research projects or be utilized by other educational institutions. In psychology, clinical practice and research are often compared to “two wheels on the same axle,” a metaphor I believe applies to other fields as well. Both are essential to move forward. Until graduate school, I was solely engaged in research without clinical experience, and I keenly felt the need to accumulate clinical experience to make my research more impactful and practical.

Being a faculty member at the JAIST Health Care Center, I conduct research alongside my clinical practice in student counseling services. My journey to this point has been full of twists and turns, but I am now fortunate to work in an environment where I can address the mental health of graduate students as both a clinician and a researcher.

── Do you have any advice for university faculty members who inevitably grapple with the mental health challenges of their students?

Sasaki My advice is, “Don’t try to bear everything alone.” Supporting students is no easy task. I must say JAIST is quite exceptional, with half of its students coming from outside Japan, but student bodies everywhere are becoming increasingly diverse these days. This diversity makes it difficult for individual faculty members to address issues on their own. I encourage my fellow faculty members at JAIST to communicate with one another to monitor how students are doing, as I believe collaboration is key to addressing individual cases effectively. For example, they can work together with the Student Counseling Services office and other supporting organizations to come up with solutions or collaborate with other faculty members, while ensuring proper handling of sensitive information.

My research revealed that fostering a positive future orientation is crucial for maintaining mental health. To this end, we can establish a process of engaging with students, that is, helping each student recognize how much they have achieved in their learning and research activities at university, what areas still need improvement, and genuinely feel that they are accumulating successful experiences. And I believe this form of support—nurturing their mindset—is something uniquely within the faculty’s capacity to provide.

Daily Training to Acquire the Skills One Lacks

── What brought you to choose college students’ mental health as a research subject?

Sasaki As a college student, I was able to perceive my growth through feedback from senior students and professors and casual conversations in laboratories. This made me want to trade places and start supporting students myself. By nature, I’m fond of animals and became interested in the behavioral principles of animals, including humans. As an undergraduate student, I studied psychology as part of a behavioral science course at Kanazawa University. After learning the basics of psychology, I paused to consider what I wanted to pursue in graduate school. I chose a then-emerging academic discipline called health psychology, which focuses on promoting health. This led me to enter Naruto University of Education in Tokushima Prefecture. At the time, I was thinking about whether there was something I could do for patients before their conditions became serious.

There, my primary research topic was “stress coping,” which explores how individuals act and respond when under stress. In the second year of my doctoral program, I successfully completed the survey study I had planned. However, I began to worry that I might end up building an empty theory if I continued my research without engaging in clinical practice. To address this concern, I decided to seek guidance from Dr. Yoshihiro Kuno, one of my mentors from my undergraduate years.

At the time, Dr. Kuno was with Chukyo University, Nagoya. Under his supervision, I began offering student counseling as a part-timer on a weekly basis. That was my first encounter with student counseling. In retrospect, having to put together my doctoral thesis while doing a clinical apprenticeship proved to be a valuable experience.

Of all the clinical fields available, I was most interested in medicine, so I decided to take a position as a medical staff member at the Center for Mental Health Care, Nagoya City University Hospital. One of my responsibilities there was conducting preliminary examinations for outpatients, which involved interviewing patients before they saw a doctor. This experience, which allowed me to understand the role of medical staff who first interact with patients in a hospital setting, has been highly beneficial in my work with the student counseling service that I started later.

I thought it would be essential to gain on-the-job knowledge at medical institutions if I were to support college students someday. While offering support to students, we may find it necessary to collaborate with medical professionals. Being able to determine at what stage to involve them is crucial. It is also important to know what information medical practitioners need to make an accurate diagnosis or decide on a treatment plan. I attribute who I am today to that invaluable experience in a medical setting.

To Perform Well, One Must Know How to Balance Work and Rest

── Before coming to JAIST in 2013, you had pursued a variety of careers, gaining diverse experiences.

Sasaki I believed it was important to gain as much clinical experience as possible, working with patients of all ages, from children to the elderly. Through numerous fortunate opportunities and the generous support of others, I was able to acquire the skills I felt I needed at the time. Looking back, every experience was invaluable, but I must admit I was relieved when I secured a permanent position at JAIST.

── Is there a good recipe for building a successful career both as a clinician and a researcher?

Sasaki I think it’s about working with purpose and relaxation in balance. In my case, as soon as I finish my day’s work and sit in the car in the parking lot, my mindset shifts instantly, like flipping a switch: No more thoughts about work. On the other hand, when I leave home by car and step out at the office, my mindset shifts back the other way.

For some time after I took the position, I often worked at my office on weekends. However, as a clinician, I have to interact with others. As such, I’m expected to make level-headed decisions every day. Therefore, I need to consistently conserve my energy and ensure I maintain a well-balanced life.

I make the most of my downtime to maintain a good physical and mental state. For leisure, I enjoy driving my stick-shift car while listening to my favorite music, indulging in food adventures across Ishikawa Prefecture, or gardening. But I feel most comforted when I’m with my four beloved cats. My deep desire to truly understand animals even led me to earn a Level 1 Pet Care Adviser qualification from the Japan Pet Care Association. When I retire from research, I will gladly dedicate myself to doing something for animals, who have brought so much color to my life.

| By My Side |

Living with her four beloved cats, Dr. Sasaki has their photos displayed in her office. “They all came from different backgrounds and have different personalities. The cats constantly teach me what it means to “live” and remind me of where I first started as a psychology student.” |

|---|---|

| This Book |

Published in 1963, this classic on ethology combines humor and insight from a renowned researcher of “imprinting,” a process most famously observed in ducklings that perceive the first moving object they see after hatching as their mother. “This book was recommended to me by Dr. Yoshihiro Kuno, whom I met by chance at a university I visited without an appointment while considering which universities to apply to in my second year at high school. Later, he became my clinical advisor. Dr. Lorenz’s storytelling showcases his exceptional animal observation skills and deep love for animals, which never fail to make me smile.” |

Megumi Sasaki

Associate Professor, Health Care Center, Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. Certified Public Psychologist and Certified Clinical Psychologist. Born in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. After receiving her bachelor’s degree from the Department of Behavioral Science, Faculty of Letters, Kanazawa University in 1998, she continued her studies at the Naruto University of Education Graduate School of Education and received her Ph.D (Education) from the Hyogo University of Teacher Education. After serving as Research Fellow, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Research Fellow, Department of Psychiatry, Nagoya City University Medical School, and Associate Professor, Naruto University of Education Center for the Science of Prevention Education, she assumed her current position in 2013.

Interview and original article: Izumi Kanchiku (team Pascal)

Photo: Shina Matsumura

Cats (Photo courtesy of Dr. Sasaki)

Cats (Photo courtesy of Dr. Sasaki) King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz, translated by Toshitaka Hidaka, Hayakawa Publishing Corporation.

King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz, translated by Toshitaka Hidaka, Hayakawa Publishing Corporation.