3S is the abbreviation for “Seiwa Scholars Society,” which consists of the past and current Inamori Research Grant recipients. The 3S has evolved since 1997 with the hope that the interactions among the various specialties of the 3S members can lead to the further development of the research of their own. In the series “Visiting 3S Researchers,” we interview researchers in 3S who are very active in a variety of fields. Our seventh interviewee is Dr. Hajimu Hayashi (2009 Inamori Research Grant Recipient) from the Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, Kobe University.

A new-born baby cannot do anything by itself. As it grows, however, it begins to roll over or stand up on its feet. It is not just its body that grows; its mind develops as well. In the first place, how is a child’s mind different from an adult’s? We invited Dr. Hayashi, who is studying the child mind using lies as a lead, to give us a detailed account on this topic of great interest.

── How does the study of “lies” tell you about a child’s psychological development?

Dr. Hayashi (title omitted below) Lies are very familiar to us. We constantly tell small lies, concealing our true thoughts in order not to make waves. Some psychological studies have reported that humans tell lies every day. Meanwhile, to survive in this world, it’s very important to be able to judge between right and wrong in what others do and to be able to see through lies, because you sustain disadvantages if you cannot. For these reasons, lying is closely connected to social skills. I’m trying to discover how children understand lies and at about what age they begin to tell complex lies, with the aim of establishing indices with which to assess the social skills of the child mind.

── In what sense do children and adults understand lies differently?

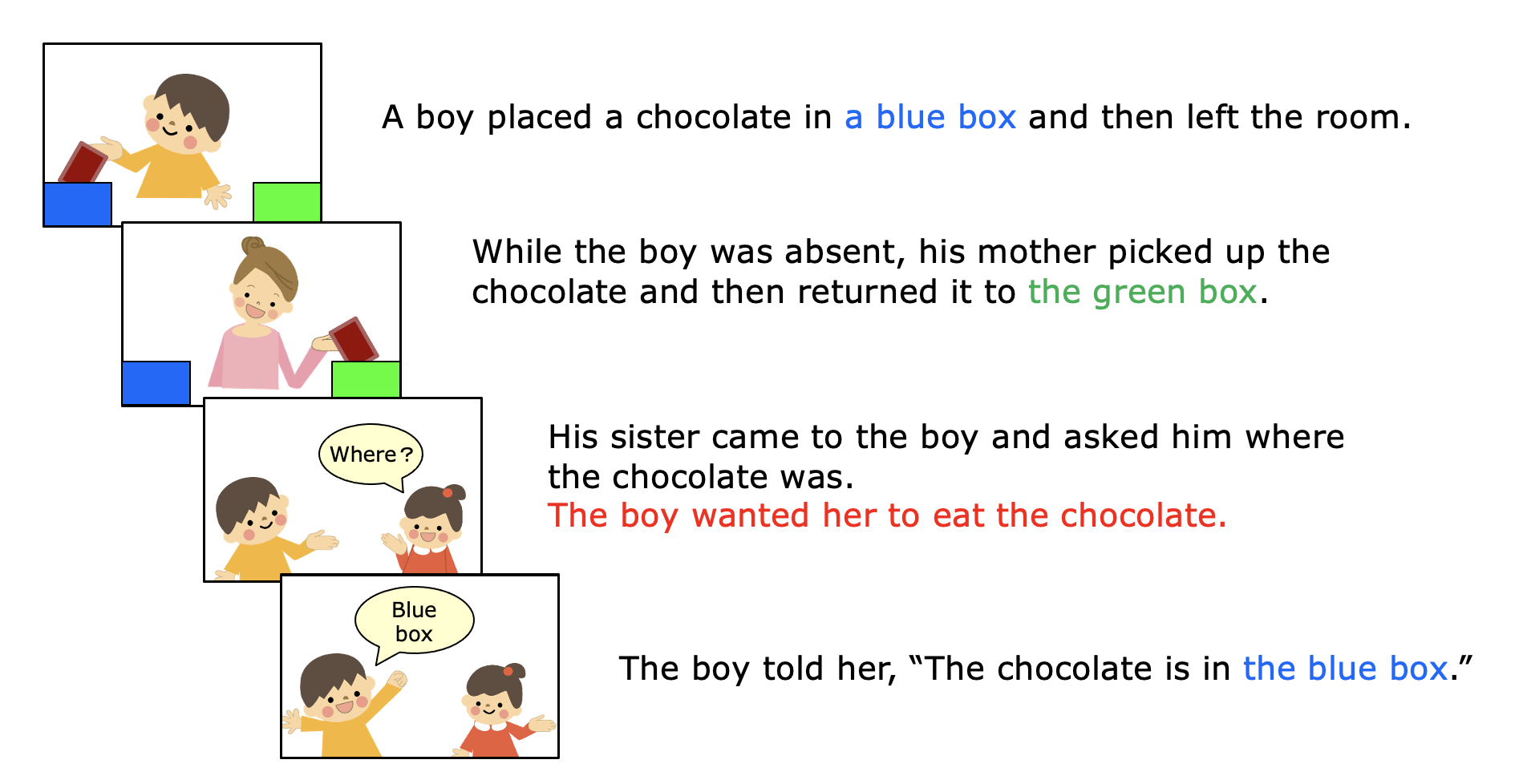

Hayashi If we psychologically analyze on what grounds an adult concludes that someone’s statement is a lie, it is not enough that “the statement is false.” It is also necessary that “the speaker believes the statement to be false” and that “the speaker intends the listener to believe that the statement is true.” One needs these three things before they can say someone is telling a lie.

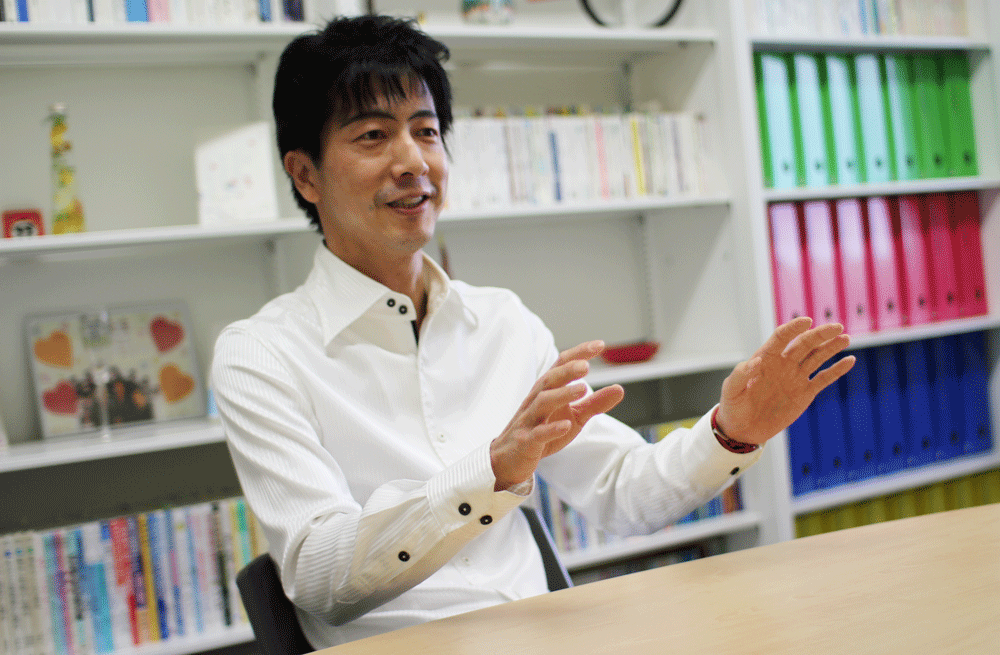

I want you to take a look at the illustrations below.

Suppose a boy placed a chocolate in a blue box and then left the room. While he was absent, his mother came into the room and moved the chocolate to a green box. Now, the boy still believes that the chocolate is in the blue box, right?

If the boy tells his sister that the chocolate is in the blue box, wanting her to eat the chocolate, do you think that this makes him a liar? Adults generally decide that he is not telling a lie as he doesn’t know that the chocolate has been moved to the green box. But many children between the ages of four and six think otherwise. In other words, a child’s attention is liable to be drawn to the discrepancy between the boy’s statement and the fact that the chocolate is not in the blue box after all, rather than considering the boy’s intention when he said, “It’s in the blue box.”

We did this experimentation with first graders, fourth graders, and adults*1 and found that the same phenomenon occurred with about 30% of first graders. The boy intended to tell her the truth but, as it turned out, made a remark that ran counter to the truth. Given this situation, they concluded that the boy had “told a lie.”

As this study demonstrates, small children may decide that the speaker tells a lie if the statement turns out to be contrary to fact, regardless of whether or not the speaker intended to deceive them. If you’ve ever raised children, you might have felt mystified when your child called you a liar even though you hadn’t had the faintest idea that you had told a lie. In such an embarrassing situation, if you know that children perceive lies differently than adults do, you can interact with your children in a different light.

── I believe how and when children tell a lie changes as they grow older. Could you tell me how the change occurs?

Hayashi The earliest lie that you are most likely to encounter is a simple lie that children tell to avoid punishment. Reports say that it starts between the ages of approximately 30 and 36 months. For example, they tell such a lie when they eat something on the sly. When asked, “Did you eat it?,” they shake their head “no” or they say “I didn’t,” apparently trying to avoid punishment.

Other than the simple lies that we tell when we deny what is being asked, we tell a lie intentionally in an attempt to give a mistaken idea (false belief) to others. A good example of this is an “Ore, ore (it’s me, it’s me) scam,” in which a person calls senior citizens to solicit money by giving them a false belief that the caller is their grandchild. Now, we know that it is hard for three-year-old children to tell such a lie. To give someone a false belief, you need to imagine what is on their mind and predict their reactions, namely, what they do not know and what they might think and do. Psychologists call this—the capacity to understand other people’s behaviors by attributing mental states to them—”theory of mind.” It is believed that this capacity develops greatly at the age of four or five and that children begin to tell intentional lies distinctly at about the age of five.

── What method do you use to find out how children tell a lie?

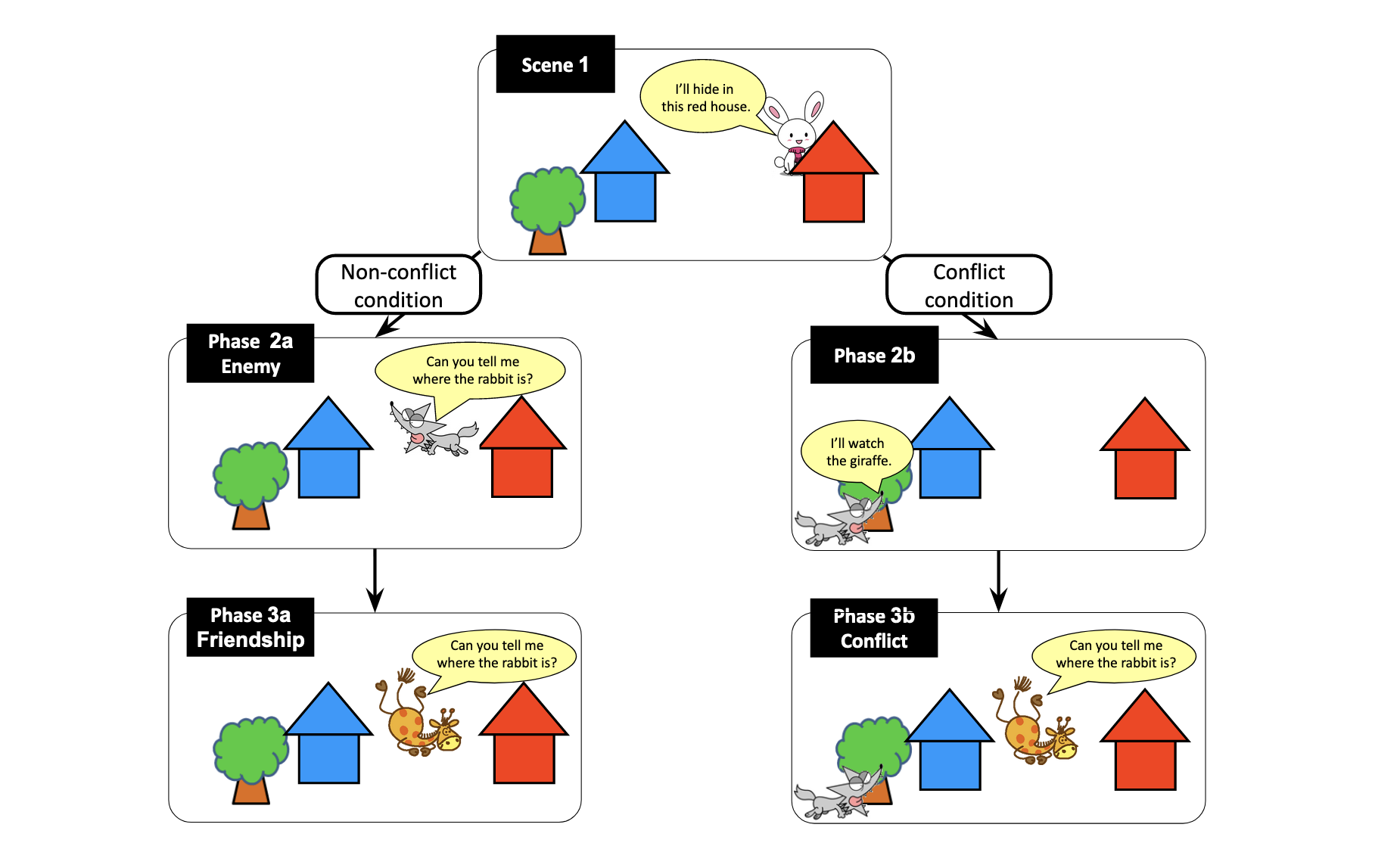

Hayashi Depending on what they wish to pinpoint, different researchers use different techniques of their own creation. Let me give you a glimpse at what we did.*2 We presented a puppet show to kindergarteners between the ages of four and six. For each play, we invited one child only.

The play started with a puppet rabbit, who spoke to the child, “I’m waiting for my friend giraffe to show up, but I’m running away from a wolf. I’ll hide in the red (or blue) house. Please protect me.” The child then promised they would and the rabbit hid in the red (or blue) house. Then came a wolf, asking the child, “Where’s the rabbit?” Many of the four-year-olds found it hard to tell a lie and obediently told the wolf where the rabbit was, whereas the five- or six-year-olds lied and pointed at a house where the rabbit wasn’t or chose not to answer the wolf, thus successfully protecting the rabbit. When the wolf had left and the friend giraffe showed up to ask where the rabbit was, they were able to indicate the house where the rabbit was. This experiment clearly showed that the ability to tell a lie varies with age.

But not all situations where we might need to deceive someone are as simple as this. So, we tried more complicated situations where the child is supposed to sense the conditions, which is shown to the right of the following illustrations. The wolf hides from the giraffe and eavesdrops on the conversation and only the child knows that the wolf is there.

(Kodomo no Shakaitekina Kokoro no Hattatsu (translated title: Development of Children’s Social Mind), Hajimu Hayashi, Kanekoshobo, 2016)

When an adult is in this situation, a conflict arises in them: They want to tell the giraffe where the rabbit is but cannot because the wolf is there and will eavesdrop on the conversation. Under this conflict condition, even six-year-olds told the giraffe where the rabbit was right away, when asked.

── Do they really understand that they shouldn’t let the wolf know?

Hayashi Many of them do, yet they end up telling the truth. For one to tell a lie, they need not only to use theory of mind but they also need to control themselves not to spill whatever information they have by reflex. In some cases, it is also necessary for them to intentionally convey false information instead. In a nutshell, you need to have control over what you do. We call this ability to control one’s attention and behavior “executive function.”

As with theory of mind, executive function begins to develop between the ages of four and five. When they are not feeling any conflict (“non-conflict condition” in the illustration above), they can deceive a wolf with their lies. Yet, their faculty to deceive others is limited at this age and they tell the truth on the spur of the moment under the conflict condition. What this means is that they do not understand sufficiently that, if they convey something to the ally (giraffe), it will be conveyed to the enemy (wolf) as well. In other words, they do not get the idea of “sharing information with allies” in the true sense of the phrase. When you speak with a child and someone else is nearby, sometimes the child might startle you when they mention something that you don’t want that nearby person to know. You say something like, “How come you’re talking about that now?” These results of the experiment should tell you that it happens for a reason.

Interestingly, no matter how many times they were asked by the giraffe, some children kept silent and did not answer until the wolf gave up and left. Others actually whispered the truth to the giraffe, saying, “I’ll tell you in a quiet voice because the wolf is here.” We were impressed to know that they behaved flexibly, reading between the lines. What we witnessed was the very process of children’s social skills developing.

── What else can we learn by studying lying?

Hayashi Because I’m intrigued by how children’s social mind develops, I’m also studying the development of their morality. When someone has told you a lie, you need to determine if it is a lie or not and if it is good or bad, the latter of which requires moral faculty. In a research paper I published in 2021,*3 I explored how children’s morality develops with lying as a clue.

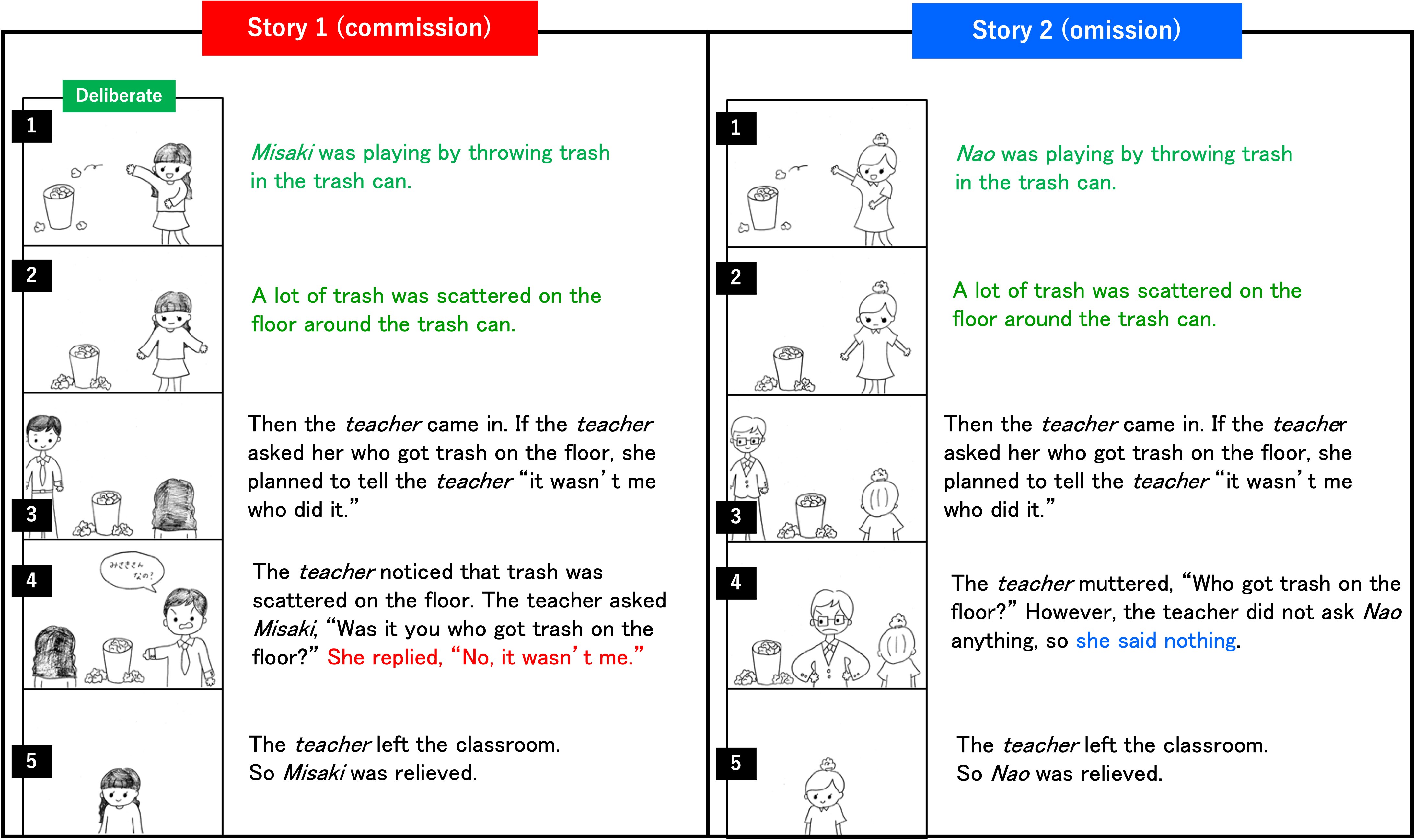

To three age groups of participants—third-graders, sixth-graders, and adults—They were presented different scenarios and were asked whether they thought each case was good or bad. The illustrations below are a pair of the scenarios presented to them. Now, the key point of this research is the two different types of lies: lies of commission and lies of omission.

(from Kobe University’s press release)

A lie of commission means, for example, to say “I didn’t do it” when you actually did it, while a lie of omission means to say nothing when you did something. Viewed objectively, both protagonists (girls in this scenario) have the same intention and both stories ended with the same consequences. Therefore, both are equally bad, but adults have a tendency to judge a harm caused by taking action more negatively than an identical harm caused by not taking action (less concerned with the latter than the former). This is called “omission bias.”

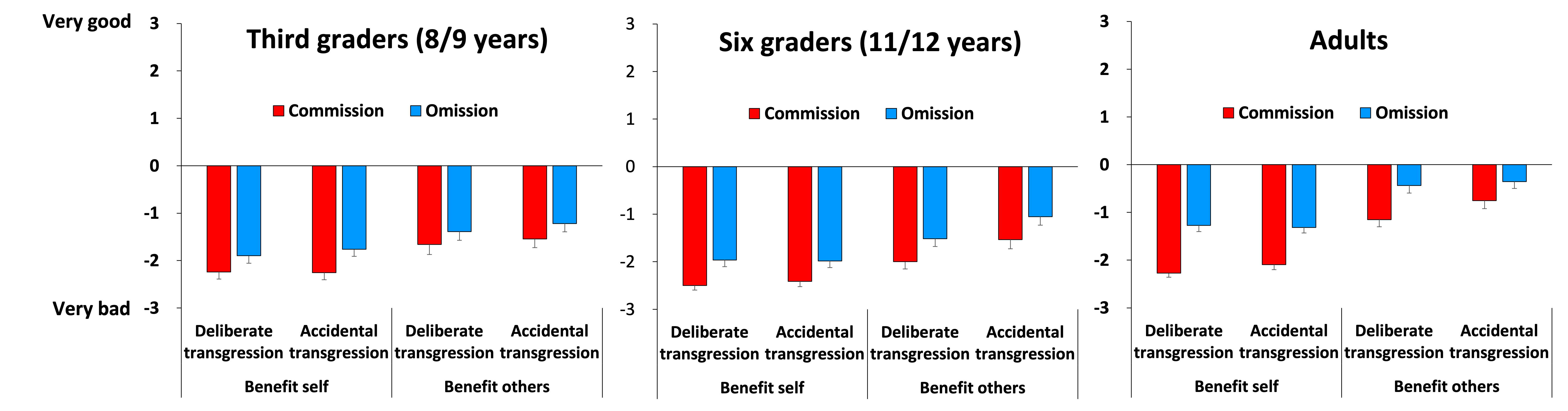

We then investigated whether such bias appears in varying degrees among different age groups. As shown in the graphs below, all age groups judged lies of commission to be worse than lies of omission, indicating that omission bias in moral judgments of lies occurred in children as well as in adults. Furthermore, it was found that the older the participants were, the greater the difference in the degree of bias became, overall, between the two types of lies, resulting in stronger degree of omission bias. This indicates that a child’s moral judgment of lies changes as the child gets older and that this change continues over a long period of time.

── So, omission bias is greater in adults than in children, right?

Hayashi Yes, you nailed the important point. In some instances, choosing not to tell the truth is as bad as intentionally telling a lie. Adults have the obligation to tell this to children, but chances are that adults themselves are not aware of this because of their own bias. If adults do not know about omission bias, they may not be able to give children proper guidance when they absolutely have to do so.

── Could you tell me what brought you to study psychology?

Hayashi When I was at high school, I had no idea about my future career or what occupation would be a good fit for me. But people told me that studying STEM would broaden my views and increase my career opportunities and so I decided to major in science for no particular reason.

Then some books I read after getting into university made me realize I was interested in education and human psychology and I transferred to the faculty of education. At that time, I didn’t have much contact with children in my immediate circle, and I didn’t particularly like children. When I was a junior student, I had an opportunity to visit a kindergarten as part of a seminar of the faculty program, where I had an impressive experience. There was a five-year-old girl who wasn’t that cooperative with the task I had asked the children to do, and so I promised her that I would play with her after the task was finished. However, because I didn’t have time to play after the day’s task was over, I went straight back to my university. Then, when I visited the kindergarten the following day to continue with the task, that girl found me and called me “a liar.” It was indeed heartbreaking but I was impressed nonetheless to know that a five-year-old had an awareness of the concept of “lying” and I was intrigued by the development of children’s psychology. Psychology is a mixture of science and the humanities, which I think suits me very well.

── Are you interested in joint research with researchers from other fields?

Hayashi I’d love to, when I have an opportunity to. At this moment, I don’t have such opportunities, but I’m working more closely with people from educational institutions, such as school and kindergarten teachers. Actually, I have many chances to work with high school teachers. One of the fruits of such collaborations was a book titled “Tankyu no Chikara o Hagukumu Kadai Kenkyu (translated title: Research of Problems that Foster the Inquiring Mind),” which I co-edited with Kobe University Secondary School. Published in 2019, this academic work showcases model practices of inquiry studies at secondary schools.

I’m not interacting with children face-to-face as a teacher, so there must be many things that I’m not aware of. School teachers and caregivers help me to see these things. In return, I share my research findings with them or invite them to witness my experimentation, which they say gives them an opportunity to see aspects of their children that usually remain unseen.

Children’s responses are full of unexpected surprises, and they always amaze me and never cease to impress me with their unpredictability and cuteness. I still find myself excited about responses I would get when I visit kindergartens or elementary schools for research. Development of communication and social skills may seem complicated, but they are not that elusive. If you use your ingenuity by, say, using the act of lying as a clue that I have talked about, you’ll get to see how humans and children think and act. That’s the beauty of psychology, I think.

── Human psychology is so interesting. Thank you, Dr. Hayashi, for these most fascinating stories.

| This Book | “Origins of Human Communication” by Michael Tomasello A classic book on comparative cognitive science, whose Japanese translation was published in 2013. “Based on the findings from research on children and chimpanzees, this book describes how humans have become able to behave socially by presenting a variety of evidence. I found this work so irresistible that I put so many sticky-notes as I read. This was also a useful reference when I wrote Kodomo no Shakaitekina Kokoro no Hattatsu (translated title: Development of Children’s Social Mind) published in 2016.”  |

|---|---|

| Unchosen Path | Occupations that have to do with the sky Dr. Hayashi said he first took an airplane when he was 19. “I went to Canada and the sight of the Canadian Rockies from the plane window was so beautiful and moved me a lot. Ever since then, I have had a yearning for the sky. I could have been a pilot or flight attendant, or, if I’m capable, I may have wanted to be an astronaut.” |

Hajimu Hayashi

Professor, Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, Kobe University. Received his undergraduate degree from the Faculty of Education, Kyoto University, and Ph.D. in Education from the Graduate School of Education, Kyoto University. JSPS Research Fellow. After serving as a Full-time Lecturer and then Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Education, Okayama University, Dr. Hayashi has assumed the position of Associate Professor in 2013 and Professor in 2021 (to present) at the Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, Kobe University. His areas of research include cognitive development and educational psychology. In addition to his research work, Dr. Hayashi is actively involved in education by serving as an advisor to super science high schools and authoring “Daigakusei no tame no Research Literacy Nyumon (translated title: Introduction to Research Literacy for University Students).” One of his most important publications to date is Kodomo no Shakaitekina Kokoro no Hattatsu (translated title: Development of Children’s Social Mind, published by Kanekoshobo).

Interview and original article by Izumi Kanchiku (team Pascal)*The interview was conducted online.

Photos and figures provided by Dr. Hayashi